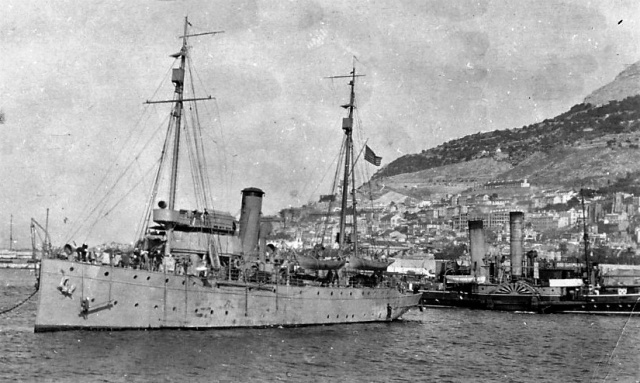

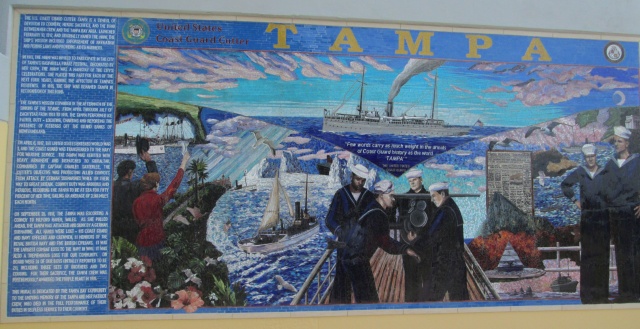

HISTORY OF PASCO COUNTYThe Sumner Family of Pasco CountyJesse Carey Sumner and Robert and Alexander Sumner Two great granddaughters of Jesse Carey Sumner, who are said to have settled in Pasco County near Clay Sink in 1838, are sharing the results of their research about the Sumner family. The authors are Joann Sumner Bandy and Susan McMillan Sheldon. Joann is the granddaughter of David Edwin Sumner and lives in Clearwater. Susan is the great-great granddaughter of Nancy Elizabeth Sumner and lives in Dade City. Susan works as substitute school teacher and is a volunteer at the Pioneer Florida Museum. Joan Sumner Bandy used these sources: a letter on the early history of Pasco County by her grandfather, David Edwin Sumner; information givcn to the Pioneer Museum by Judge Robert Sumner; the book Jake Summerling, King of the Crackers, by Joe Akerman, Jr. and Mark Akerman; and interviews with Susan McMillian Sheldon, great-great granddaughter of Nancy Elizabeth Sumner. This article first appeared on the EPHS web site. Jesse Carey, the second son of John Sumner and Mary Hogan, was the first Sumner to come to Florida. He was born in 1819 in Emanuel County, Georgia. When he was 21 in 1838, he heard that there were cattle in Florida free to any man that could corral and tame them. So, he left home, a working plantation with 160 slaves, and unwittingly located in the northeastern part of (now) Pasco County. But, alas! Things were not as he had dreamed. Cattle, yes, the woods were full of them – there were also five wild Indians for every cow in the woods. His nearest neighbor lived twenty miles to the north. There were a number of cattle herders in the state but none had located near him since the area was considered an Indian Rendezvous. His place soon became the headquarters for other cattlemen since there was a large quantity of cattle in that section, and the fine grass range. The Indians were not happy with their new neighbors and trouble started in earnest. The Indians would do whatever they could do to torment them. They particularly liked to torment the settler’s family whenever the man was away from home since that hurt the husband more that tormenting the man himself. After living in such torment for two years, Jesse was forced to go to Ft. Marion in Ocala to get away from the Indian atrocities for a year. Jesse found love when he retreated to Ft. Marion in Ocala. He married his sixteen year old neighbor, Caroline Hall in February 1845. After returning to the Clay Sink area, they acquired a neighbor ten miles away. Unfortunately, the father died and the mother asked the Sumners to take care of their son. The Indians had been friendly and peaceable; all seemed well. Their fears vanished. Those days rope for lassoing cattle was extremely scare and cost a great deal. Therefore, it was necessary to own the rope together. His neighbor ten miles away needed the rope on a certain day. He placed the boy, Dan Hubbard, on the horse and directed him to take the rope to the neighbor. The start was made in early morning. When night came, the boy had not returned. Jesse set out to find him and upon arriving at the neighbor’s house, he learned that the boy had not been there. They immediately started a search and tracked the horse to the Little Withlacoochee River. This is the spot where the Indians had hidden beside a large tree and had taken the boy and the horse. In the meantime the horse came in with boy’s suspenders platted in its mane, which was a message from the Indians to Jesse that they had the boy. During this time, men gathered from far away and a general search was made. In their book Jacob Summerlin, King of the Crackers, Joe and Mark Akerman said that Jake “gathered” three unbranded ponies that were with his herd on open range territory. The ponies actually belonged to three Indians. The Indians claimed that the horses had been stolen and that the child had been kidnapped in reprisal. The Seminoles living in the area assisted in finding the three Indians. The three Indians confessed that they were present when the boy was killed and his scalp taken, later, to be presented to their chief. They were given an ovation for taking the scalp of a white man. The three Indians captured were placed in a temporary log jail for keeping until further investigation. During the first night, they stripped their buckskin clothes, made rope and hung themselves and were all dead when found the following morning. It was a custom in those days with the Indian never to die by the hands of a white man if he could avoid it. This ended the search for the boy and a general drive was made upon the Indians. Summerlin was so distressed over the kidnapping that he wrote to Governor Thomas Brown complaining about the activities of the Indians in his area. “They are on our ground there is no doubt, and you may suppose our feelings when we send a child on an errand or to school. We are getting tired of waiting to see what the government will do, and we calculate to scout until we are satisfied what has become of the child, and I fear if we find that child in there (sic) possession there will be a fight if they don’t give him up.” The scalping of his foster son was one of the events that lead to the third Seminole War. Jesse served with distinction in Captain William H. Kendricks’ division. It also caused the final removal of most of the Indians to the Everglades, and the clearing out of Indians brought several new settlers into the Pasco County section. The first dedicated school house ever built in Pasco County was erected by Tony Sumner, John Sumner, Cary Sumner, Alec Sumner and King Joseph Sumner. Their ages ranged from 18 to 24 years at the time they built the school and attended school three months which was all the schooling any of they received, each paying the teacher his portion. The teacher was paid $35 for the session. Jesse’s younger sons attended Emory University. The Sumner Family in Dade CityThis article was contributed by David E. Sumner “Sumner” is an old English name based on the occupation of “summoner”—a sheriff’s messenger who served summons and citations to appear in court proceedings. Dade City, Florida, has historically been home to at least three branches of the Sumner family. Growing up in the 1960s, I knew the other two as the Edsel Sumner branch and the Robert Sumner branch. Among eight pioneer Sumner families recognized during the re-dedication of the Pasco County Courthouse on Dec. 5, 1998, three of them were part of our branch: David Edwin (hereafter referred to as “D. E.”) and Frankie Thrasher Sumner, Jesse Cary and Caroline Hall Sumner, and King Joseph and Susan McMinn Sumner. My great-great grandfather, Jesse Cary Sumner, was born in Richmond, Virginia, and came to Dade City in 1838. His brother Alexander Chestnutt Sumner came here in 1841 and half-brother Robert Lawton Sumner moved here around 1864. A History of Pasco County, which was edited by J. A. Hendley, contained an article written in 1927 by my grandfather D. E. Sumner (1874-1937). I will quote from the most interesting parts. He wrote: “My grandfather Jesse Cary Sumner [1820-1871] was born near Richmond, Virginia. His father moved to Georgia where my grandfather lived until about 1838, at which time he heard of Florida as a country full of wild cattle free to any man provided he could corral and tame them. But alas! Things were not has he had dreamed. Cattle, yes, the wood were full of them—there were also five Indians for every cow in the woods,” he wrote. “Of course, the white man’s activities soon provoked the Indians into hostilities and trouble started in earnest. It was necessary for my grandfather to. . .keep a large pack of vicious watch dogs on hand at all times for his family’s protection.” D. E. Sumner goes on to describe several brutal skirmishes and killings that occurred in the 1840s between the white settlers and the Indians. “The Indians had a way of scaring women and children…they preferred to capture and kill his children, as the Indian seemed to realize that such persecution was more effective than killing the man,” he wrote. “At the time the Indians were driven out, my grandfather decided to move and located two miles east of Dade City, where he acquired a large body of land, at which time he had six sons and four daughters and they all entered into farming,” he wrote. The father of D. E. Sumner was King Joseph Sumner (1850-1920). King Joseph’s brother, William Chestnutt Sumner, was publisher of the Fort Dade Messenger, Pasco County’s first newspaper. According to Webb’s Historical, Industrial and Biographical Florida (1885), the newspaper was established in 1882. When King Joseph Sumner died on July 23, 1920, the Tampa Tribune obituary named ten surviving children: D. E. Sumner of Dade City; Marion Earle Sumner of Clearwater; Lawrence Sumner, Yancey Sumner, Miss Ella Sumner and Mrs. E. L. Randall, all of Tampa; Mrs. A. J. Drew of Homestead; Mrs. W. L. Fulton of Savannah; Mrs. J. W. McDonald of Wauchula, and Mrs. A. E. Edwards of Los Angeles. A copy of the “Manual of the College Street Baptist Church” (now First Baptist Church) dated Jan. 1, 1907, indicates that John R. Sumner, William Chestnutt Sumner, J.D. Sumner, and G.N. Sumner were all deacons. Other deacons included David O. Thrasher (my great-grandfather), O.L. Dayton, M.F. O’Neal and Fred Hack. Other historic Pasco names included in the 1907 directory were: Coleman, Dayton, Embry, Hendley, Larkin, Mobley, Sistrunk, Tait, Touchton, and Thrasher. At the time of his death in 1937, D. E. Sumner lived in Winter Haven, where he was district sales manager for the Virginia-Carolina Chemical Corporation. His obituary was published in Dade City on April 26, 1937, and read: “Mr. Sumner was born sixty-two years ago in a log house a mile east of the present site of Dade City. . . .He received his schooling in this county and entered the citrus business here when a young man, raising a large acreage of groves known as some of the finest in the county. … “He was first married to Miss Frankie Thrasher [1880-1922] of South Carolina who passed away a good many years ago (see separate article on Thrasher family). Their three children are Edwin M. Sumner [1897-1963], Joe Sumner [1913-1959] and Mrs. Susie Bugbee [1902-1989], all of Dade City.” D. E. Sumner left about 150 acres of land to each of his two sons, who spent their lives as citrus growers. Edwin Sumner’s land was located on Duck Lake Canal Road (off River Road about four miles east of the city) while my father’s land, where I grew up, was located off of River Road and Sumner Lake Road about two miles east. My father, Joe Sumner, lived from 1913 to 1959 and died young due to lung cancer. My mother, Ruth Sumner Hoffman, died May 11, 2011, at the age of 92. My two sisters, Joann Bandy and Frankie Goldsby, now live in Belleair Bluffs near Clearwater. I left Florida to pursue a college teaching career. The only remaining members of the family living in Dade City are Frankie’s son, Joey (and Lisa) Wubbena, and his daughter, Lyndsi (and David) Greim, who have homes on the property that have been in our family for more than 80 years. Joey has been a firefighter, city official, and served two terms as president of the Dade City Chamber of Commerce. Sumner Descendants Honor Ancestor At Tombstone DedicationThis article about Jesse Sumner (1814-18701) appeared in the Tampa Tribune on Feb. 21, 2009. By KEVIN WIATROWSKI DADE CITY – The evidence of Jesse Sumner’s presence in Pasco County is everywhere, from the names of streets to the names of thousands of people descended from him. Until last year, though, no one could say exactly where Sumner, one of Dade City’s earliest citizens, was buried. The question gnawed at Brian Sumner for two decades. “Twenty years of research, and we finally found his grave last year,” said Sumner, a retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel from Okaloosa County. Brian Sumner is the great-grandchild of Jesse Sumner, who fought in the third Seminole Indian War in the 1850s while settling what was then the frontier. Jesse Sumner’s descendants gathered this morning at the city cemetery on the east side of town to remember their Georgia-born progenitor. Two new marble headstones marked the side-by-side graves of Jesse Sumner and his wife, Caroline Hall Sumner. Jesse Sumner’s stone came from the federal Department of Veterans Affairs. Family members raised money for Caroline’s. “If there was a way for Jesse and Caroline to be looking down from Heaven, I’m sure they’d be happy to see us all here,” Susan McMillan Shelton told the dozens of relatives who assembled for the service. They sat on folding chairs surrounded by earlier generations of their family. According to Shelton, Jesse Sumner was born on an east Georgia plantation in the second decade of the 19th century. As a young man, he struck out for Florida, drawn by the promise of building his fortune by capturing the wild cattle left behind by Spanish settlers a century before. Sumner and people like him came to be known as “crackers” for the sound of the whips they used to round up the cattle. Sumner settled first in the Clay Sink area near the Withlacoochee River in what is now far northeast Pasco County. Conflicts when the Seminole Indians forced him north to Ocala for a time. It was there he met and married Caroline Hall, a decade or so his junior. Eventually the couple and their burgeoning family — they had 11 children in all — settled in the Dade City area along River Road. Jesse Sumner’s two brothers also settled in the area. When he died in 1871, Jesse Sumner was one of the first people buried in the cemetery where his relatives gathered nearly 140 years later to honor him. Grave markers for Jesse and Caroline Sumner vanished long ago, leaving behind the mystery of their graves’ locations. That mystery was solved after Brian Sumner met his distant cousin Susan Shelton through a message posted at the Pioneer Florida Museum just north of town. Over two years, and with the help of a grave dowser — a person who finds graves the way a stick-wielding water dowser finds underground water – they tracked down the spot they believe Jesse and Caroline were laid to rest. For Brian Sumner, today’s ceremony fulfilled a quest that was partly about finding an ancestor and partly about learning more about himself. “I don’t know why some people care about their roots, and some don’t,” Sumner said. “It’s wonderful to understand your history.” Reporter Kevin Wiatrowski can be reached at (813) 948-4201 or [email protected]. The Sumner Boys Go to WarThis article was contributed by David E. Sumner.  Homer and Wamboldt “Bo” Sumner were Dade City boys. Their family lived on River Road east of town, and their father, Jefferson D. Sumner, was “a well-known merchant in his day,” according to the Dade City Banner. He died in 1911 when Bo was 18 and Homer was 11. Their mother, Minnie, remarried in 1912 to Frank Brummer, and the family moved to Tampa with the boys and their brothers and sisters. The boys came from a pioneer Dade City family. Their grandfather, Jesse Carey Sumner, was one of the earliest settlers in Fort Dade. Their uncle, William Chestnutt Sumner, started publishing the Fort Dade Messenger, the area’s first newspaper, in 1882. Fort Dade was incorporated as Dade City in 1885. Homer and Bo were the nephews of my great-great-grandfather, K. Joseph Sumner, and I grew up in the same Florida town. When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Bo, 24, was working at the Exchange National Bank in Tampa, and Homer, 17, was a salesclerk at Maas Brothers. Both were eager to serve their country. “Homer wanted to serve. Like all teenagers, he felt he had to do something right away when war clouds loomed,” their niece, Mabry Sumner Cline, recalled in a Tampa Tribune interview in 1999. Homer enlisted in the Coast Guard in December. Bo was drafted but assigned to Coast Guard duty with his brother, Homer. Bo said he wanted to “look out for his little brother.” Both brothers were assigned to the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Tampa, and Bo was officially designated as the “ship’s writer.” Homer was the first gunner’s mate. Tampa, which was originally named USCGC Miami, was built at the Newport News Shipyard in 1912, was 190 feet long and weighed 1,050 tons. From 1912 until 1917, the ship and its crew members visited Tampa and participated in the annual Gasparilla Festival. “In honor of her close and friendly relationship with Tampa, Miami was renamed Tampa on February 1, 1916,” according to Remember the Tampa! The book said, “Tampa was one of six cutters selected in July 1917 for overseas convoy duty in the North Atlantic because of its large coal bunkers and water tanks, which allowed for long-distance cruising. Tampa escorted 402 merchant ship convoys between Allied ports during the war.”  On September 15, Tampa left for Europe to protect supply convoys from submarine attacks. Bo Sumner wrote a letter from onboard ship to his brother in Florida, which was published in the Tampa Times on October 3, 1917: “We sure were glad to get your letter for we have not heard from home in such a long time. We are both getting along fine these days and hope that you are all the same. It sure has been warm here this summer…. How are you and all? I was glad to get grandmother’s letter for I was wondering how she was these days for I had not heard from anyone in such a long time. I sure would like to walk in and see you all for a little while anyway, even if I could not tarry long, but suppose that I will have to wait until the war is over and, from the looks of things, I don’t think it will be very long now. I hear over here that it will be over in six months, but you can never tell, can you? Well dear, there is no news that I can tell you, will close for this time and give our love to…all at home. With love to you and all. Your sailor boys, Wamboldt and Homer.” On September 26, Tampa was part of a 32-ship convoy sailing out of its home port at Gibraltar. It slipped away from the convoy for reasons that are not clear. Sailing alone near sundown between Wales and southwest England, Tampa was sighted by the German submarine UB-91. At 8:15 pm, UB-91 launched a torpedo, which blasted a hole in Tampa’s hull. A second explosion followed. Tampa sank with no witnesses and no survivors. The victims included 111 Coast Guardsmen, four Navy men, and 15 British Royal Navy men and dockworkers. During wartime, the Coast Guard was under control of the Navy Department. When Tampa did not arrive at the expected time, a British seaplane and two Royal Navy PC boats went out to search for it. Three days later, the seaplane was the first to spot an eight-square-mile debris field. The Navy sent a telegram to Mrs. Brummer and other victims’ families on October 3: “The Navy Department has been informed of the loss of the Tampa with all officers and men on board on Sept. 26 off the English coast in the Bristol Channel. The reports indicate that the boat was sunk at night by a torpedo while engaged in escorting a convoy. The vessel which conducted the search in the vicinity found large quantities of wreckage and one of the Tampa’s life belts.” On October 4, the Dade City Banner carried the bold front-page headline, “SUMNER BOYS ARE LOST ON TAMPA,” and sub-titled, “Vessel Torpedoed off English Coast and Sank with Entire Crew.” The war ended a month later on November 11 when President Woodrow Wilson signed the armistice with Germany A few months later, Mrs. Brummer received a long letter of sympathy and appreciation from Giles C. Stedman, who was the ship’s writer on the USS Ossipee. The letter was published in the Tampa Times on April 2, 1919. Stedman wrote, “I only knew one of your sons, Wamboldt, and I called him Sumner, and he called me Stedman. I first met Sumner in February 1918 and from then on, I saw him whenever the Ossipee and Tampa chanced to meet.” He said that the most enjoyable time they spent together was in August when the Tampa and Ossipee were both docked at Gibraltar. Spending two nights on shore patrol together, “We were obliged to patrol the beautiful Alamelda Gardens, high up on the side of the rock of Gibraltar.” Stedman said Sumner had a “big broad smile and southern drawl” and “still lives very much in my memory as the best friend I made while serving in Europe.” Stedman told Mrs. Brummer that there was a popular store owner named “Miss Wells” in Pembroke, Wales, where Tampaand other cutters frequently docked. Wells told him that when news about the Tampa was received, “All the women and girls were crying.” Stedman asked her if she knew any of the boys from the Tampa. “She said all the girls here used to know one fellow, I think his name was Sumner, and they called him ‘Bo’ because he was so fat and always smiling. We used to love to hear him talk. All the girls have been saying ‘Poor Bo’ ever since Tampa went down.” Eighty-two years after Tampa sank, its crew members were posthumously awarded the Purple Heart in a 1999 Veteran’s Day ceremony at the Coast Guard Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Family members received the Purple Hearts of their relatives, and Bo and Homer’s family later donated theirs to the Tampa Bay History Center, where they remain on public display. On February 3, 2018, the Tampa Bay History Center held a commemorative 100th anniversary memorial for the victims of the Tampa, which I attended with my wife, sister, and cousin Margaret Sumner Rials and her husband. It was a very moving ceremony that included the dedication of a mural, music by the Coast Guard chorus, and the full crew of the current USCGC Tampa, which was harbored nearby in Tampa Bay. Speakers included Admiral Karl Schulz, commander of the U.S. Coast Guard Atlantic, and Lieutenant Commander Laura Holt from the British Royal Navy. Numerous memorial ceremonies held in Tampa and elsewhere since 1918 have honored the Tampa patriots. They are still remembered and honored every day from England to Gibraltar, to Arlington Cemetery, Tampa, and Dade City, where the Sumner boys grew up.    The author acknowledges Remember the Tampa! A Legacy of Courage During World War I by U.S. Coast Guard Archivists Nora L Chidlow and Arlyn Danielson for material about USCGC Tampa. The book was published by the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office and is available free HERE. Biographical material about Wamboldt and Homer Sumner was obtained from online archives of the Dade City Banner, Tampa Daily Tribune, Tampa Times, and Tampa Bay Times published between 1918 and 2018. David E. Sumner, PhD, is a retired journalism professor who grew up in Dade City and now lives in Anderson, Indiana. Obituary of David Edwin Sumner (1874-1937)This obituary appeared in the Tampa Tribune on April 26, 1937. David Edwin Sumner, a life-long resident of Pasco County, died early Wednesday morning at the home of his son, E. M. Sumner, in Dade City. He had been in poor health since last May when he suffered a stroke. Mr. Sumner was born sixty two years ago in a log house a mile east of the present site of Dade City. His parents were Joseph Sumner and Mrs. Susan Q. McMinn Sumner, members of some of the oldest Pasco County families. He received his schooling in this county and entered the citrus business here when a young man, raising a large acreage of groves known as some of the finest in the county. He was first married to Miss Frankie Thrasher of South Carolina who passed away a good many years ago. Their three children are E.M. Sumner and Joe Sumner and Mrs. Susie Bugbee of Dade City. About thirteen years ago he married Mrs. Alice Williams of Fort Meade, who survives him. Although Mr. Sumner always claimed Dade City as his residence and spent a great deal of time at his country home near here, he lived for some years in Tampa and later in Winter Haven where for the past fifteen years he has had his headquarters as district sales manager for the Virginia-Carolina Chemical Corporation. He was one of the most valuable members of the company’s sales force and very active up until the time of his illness. His ambition, industry and splendid character made him a highly respected citizen of this community and he will be greatly missed both her and by associates all over the state. He was a member of the Dade City Masonic lodge and former members of the Knights of Pythias and Woodmen of the World. At the time of his death in 1937, D. E. Sumner lived in Winter Haven, where he was district sales manager for the Virginia-Carolina Chemical Corporation. Funeral services were held at the Methodist church Thursday afternoon with the Rev. C. M. Cotton officiating and burial was in the Dade City cemetery. The active pallbearers were Fred L. Touchton, Joe Perry Smith, John S. Burks, Guy Fountain, Stanley Cochrane, and A.J. Burnside. Acting as honorary pallbearers were J.F. Revels., W.V. Gilbert, J.A. Carper, W.S. Cochrane, John Bryant and Col. J.A. Hendley. Besides his wife and children, Mr. Sumner is survived by three brothers: H.L. Sumner and Y.E. Sumner of Tampa, M.E. Sumner of Clearwater; and six sisters, Miss Nora Sumner and Mrs. Neta Edwards, San Francisco; Mrs. Addie Drew, Clearwater; Mrs. Liddie Fulton, Savannah, Georgia; Mrs. Mary Randall, St. Petersburg, and Mrs. Stella McDonald, Wauchula. JESSE SUMNER (1814-1871). On Feb. 18, 1871, the Florida Peninsular reported that Jesse C. Sumner died at his residence in Hernando County on Feb. 12. See the Tampa Tribune article about him elsewhere on this page. JEFFERSON DAVIS SUMNER SR. (1862-1911) was born at Fort Dade on Oct. 26, 1862. On April 20, 1887, he married Mildred Roberts (1866-1941) at Dade City. He died at Dade City on June 12, 1911. On June 15, 1911, the Tampa Morning Tribune reported that Dade City “is mourning the death of J. D. Sumner, one of the oldest merchants here…. Mr. Sumner’s three sons, J. D., Jr., Wamboldt, and Mabry, came up from Tampa.” J. D. Jr. was killed in Kansas City in April 1927. W. C. SUMNER (d. 1915). On March 23, 1915, the Tampa Morning Tribune reported: “W. C. Sumner, familiarly known as Tony, one of Pasco County’s pioneer citizens, residing near Dade City, passed away this morning [Mar. 22] at 8 o’clock. … The interment will be at the City Cemetery Tuesday at 3 p.m., under the auspices of the Masons.” DAVID EDWIN SUMNER (1874-1937) was born in a log house a mile east of Dade City. His parents were Joseph Sumner and Mrs. Susan Q. McMinn Sumner. As a young man he entered the citrus business. He married Frankie Thrasher of South Carolina. Their three children were E. M., Joe, and Mrs. Susie Bugbee. After his first wife died, he married Mrs. Alice Williams of Fort Meade. He later lived in Tampa and Winter Haven, where he was sales manager of the Virginia-Carolina Chemical Corp. He died on March 24, 1937. His obituary is elsewhere on this page. ROBERT HUGHIE SUMNER (1884-1942) was born in Dade City and lived most of his life there. He was a son of Mr. and Mrs. Alex C. Sumner, pioneer residents of Pasco County. He was survived by his wife Katherine and two children by a former marriage, Robert L. Sumner of Dade City and Mrs. Corinne Peeples of Zephyrhills, a brother John C. Sumner of Tampa, and five grandchildren. A son of Robert L. Sumner was Robert Sumner (b. June 17, 1934; d., May 25, 2011), who was a county attorney for Pasco County. |