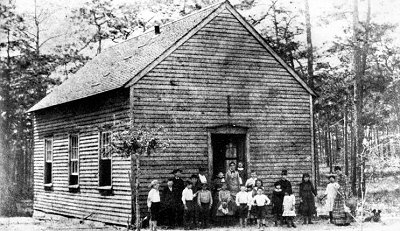

HISTORY OF HERNANDO COUNTY SCHOOLSEducational ProgressBy RICHARD J. STANABACK The following is excerpted from A History of Hernando County 1840-1976 by Richard J. Stanaback. Education probably was not given a high priority by the first settlers of Hernando County. They were undoubtedly more concerned with where they were going to stake their homesteads and how their first crops would take to the soil. As their numbers increased, and as the necessary tasks of erecting a house and planting the fields were accomplished, educational needs received greater attention. Their first efforts were simple and unorganized. Fathers, mothers, or older siblings may have sat beside younger children in the evenings for supervised drills in spelling or arithmetic; or perhaps an adult in the neighborhood, one with a little more book learning than the others, might have been prevailed upon to give some of his or her time to such instruction. But whatever the methods employed, early education in the county was rudimentary and without government support. In the 1840’s education was faring little better in other pats of the territory. In the absence of a comprehensive school program, learning was substantially a hit or miss affair. Public school facilities were almost non-existent except in the older more established towns such as Jacksonville, Tallahassee, and Pensacola. For the most part education was imparted by private tutors. Since 1839 townships had been authorized to elect three trustees to apply income from school lands to the support of public schools, but doubtless only a few scattered ones did so. Not until 1849, four years after statehood, did the Florida Legislature pass its first public school law. It authorized the construction of common schools for all white children; it was against the law to teach Blacks aged five to eighteen to read and write. The registrar of public lands was to act as State Superintendent of Common Schools and five percent of the income from the sale of public land was to be spent for education. Two years later, counties were permitted to levy school taxes on personal property; and the proceeds from a tax on the sale of slaves was earmarked for the state school fund.  The first schools to operate on a permanent basis in Hernando County were private institutions inaugurated in the early 1850’s. One was established in 1852 at Spring Hill by Frederick Lykes for the purpose of educating his son and the children of several of his neighbors, including those living several miles away at Hope Hill. Because of the constant threat of Indian attack, students whose homes were located at some distance from Spring Hill were boarded near the school. Colonel Theodore S. Coogler was the teacher at the Lykes School in 1855. Bay Port, then one of the most important settlements in the county because of its port facilities, also had a private school. So well was it managed that families were reported as moving there just so their children could attend school. And by the end of the decade, a school containing 100 students was operated in the Brooksville Union Baptist Church. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 probably put a temporary end to the county’s private schools, since fathers and older brothers were called to war, and younger children were required to help manage the farms and plantations. Then too, it sometimes took the total effort of a family to keep things going at that time, leaving little energy left for learning. In addition, most state resources were channeled into the war effort and not to the non-essentials such as education. Thus at the war’s conclusion, the educational process had to begin from scratch. In 1866, the state legislature ordered the State Superintendent of schools to support county schools with state funds. But no public schools operated in Hernando County until the early 1870s. A Hernando County Board of Public Instruction was authorized on July 24, 1869, but all attempts to organize failed until July 5, 1871 However, in 1870, the county elected its first school superintendent, Theodore Sylvestor Coogler of Brooksville. He supervised a log house school constructed on property which today is the Brooksville City Park, and another reported to have been located in the old Union Baptist Church on north Main Street. Instructors at the church school were Professors Addaholt and G. B. Ramsey. Other schools were soon started, and by 1871 there were seven in operation with a total of 237 pupils. Not all the county’s children attended, however, as there were 818 youngsters of school age. One reason for this was that Superintendent Coogler was careful to open only those schools which could be supported. Money was difficult to come by, as the county received only $600 for school expenses in 1871. Even so, three additional schools were opened in 1872. Of the ten, four operated from January to April, while the remainder followed June to September schedules. The patrons of each school were allowed to determine the time of the session, so that the children would be at home when it came time to harvest the crops. Only one school for Blacks operated in the county in 1872. It was located in Brooksville, with its seventy-two pupils being taught by a white woman of southern origin. The number of schools during the 1870’s was increased by Mr. Coogler. The total rose to sixteen in 1873, seventeen in 1874, and twenty-two by 1875. In 1873 the superintendent received $1,127 from the county and $204.50 from the state for educational purposes, of which he spent $ 1,119.01. Although many people had questioned the county’s ability to sustain public education in 1870-71, so much progress had been made by 1874 that their doubts were soon erased. Within three short years the people had come to realize the advantages of education and were showing a great interest in it. In 1874 the Hernando County Jury Presentment had this to say about the school situation:

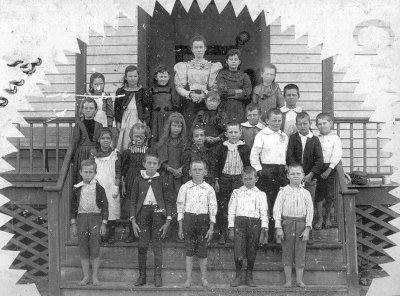

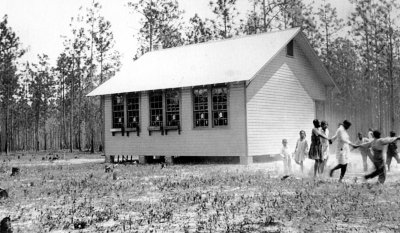

In the elections of 1875, Coogler was succeeded by J. M. Rhodes, who continued to expand the educational facilities of the county. Of a possible 1,020 students some 564, or 55 percent, were attending the county’s twenty-two schools by 1876. The average session was sixty-six days, and there were sixteen male and five female teachers, who were paid from $60 to $120 per month. Two of them had first class certificates, while four had second class and fifteen had the lowest class. Teachers’ salaries totaled the munificent sum of $1,785 for the year, while the superintendent received an annual income of $250. School buildings and school equipment were naturally of the simplest design. One early student of the Lake Lindsey school recalled the log construction and that she had sat on punchin seats (split logs with legs) and, when thirsty, had to go to the lake for a drink. The population of the county grew by leaps and bounds in the latter 1870’s and by 1880 the number of schools had risen to forty-five. The increase was partly due to their small size, the school board requiring only ten pupils for a school to be organized. However, the schools were to be located at least four miles apart. By this time, teacher salaries were based on daily attendance. But a high average had to be maintained, for if it fell below a certain level, the parents had to make up any pay the teacher had lost. Teacher institutes for the purpose of improving instruction were also developed at this time. Six Black schools, some having as many as fifty pupils, were then in existence. One of the early white schools was located at Hudson in the west central part of the county. It was a log structure built in 1881 by the settlers of that area. It was often difficult to keep warm in the school in the winter due to the chilling winds coming into the building through the cracks in the logs. The fest teacher of this school was B. L. Blackburn, and the school term, as in most other parts of the county, was three months. The number of schools continued to increase, totaling seventy-five in 1883. A. M. C. Russell, who replaced D. H. Thrasher as superintendent that year, received an annual salary of $360. In 1884, the county has 40 schools, with 1,209 pupils enrolled and an average daily attendance of 840. The number of teachers had increased to twenty-three males and fourteen females.  Another of the county’s early schools was located at Spring Lake, a community dating back to the 1840’s. It was located in a building situated on land owned by Altha Hope, near a cemetery which overlooks the lake. In the 1880’s, classes were held in the o1d Methodist Church just northwest of the cemetery. Finally, Frank Saxon donated an acre of land for a schoolhouse in 1889. When built, it contained three rooms which were large enough to hold all the students from grades one through twelve. This building was torn down in 1919 and another was constructed by the Charles Emerson Construction Company on a four acre plot on State Highway 41 across from the new Methodist Church site. The population and consequently the number of schools in the county were significantly reduced in 1887, when Pasco and Citrus Counties were carved from Hernando. In the new County of Hernando, twenty-two remained, seventeen white and five Black, while enrollment dropped to 380, 150 whites and 130 Blacks. For the year, the average daily attendance was only 300. Just twenty-three teachers were left, with an average of one teacher per school. Brooksville remained as the only principal area of settlement and the only town large enough to support a high school. Two grammar schools were situated in the Brooksville area in the 1880’s. One was located inside the city limits in the northeastern part of town on Saxon Avenue near the old Saxon house, serving the North Brooksville School District, while a second was located south of the city limits, serving the South Brooksville School District. The extension of a railroad to Brooksville in 1885 added to its status and attracted many new residents. The growth and general prosperity of the period 1ed to a proposal to consolidate the two schools and to update the system by extending education through the tenth grade. To that end, a committee composed of William E. Hope, S. W. Davis and Warren Springstead addressed the school board on October 1, 1888. In a meeting of the school board on the following day, the proposal was approved. A site committee composed of Dr. Sheldon Stringer, Frank E. Saxon, George Higgins, Warren Springstead, and J. C. Phillips was selected. Arrangements were quickly made to purchase land owned by Martha and Thomas Cook in Saxon Heights for $499. The property ownership was assumed by the board on October 27, 1888. A building was quickly erected and a four month term was instituted, with the new school being named Hernando High School on February 4, 1889. The first faculty was composed of E. R. Warrener, Principal; Mrs. E. R. Warrener, Assistant Principal with Misses Baker and Wooten as teachers. An additional improvement in the educational system occurred in 1891 when the school board approved a free textbook policy for students, due to the efforts of Board Chairman M. R. Burns.  From Images of America: Brooksville by Robert G. Martinez While Hernando was providing itself with a high school in 1889, the state was acting to provide for the return of school management to local boards. It was also during this year that the State Superintendent recommended that each county provide itself with a high school. The state continued to improve education in 1893 when newly elected State Superintendent William N. Sheats revoked all teacher licenses, requiring them to be recertified through competitive examination. He also encouraged school consolidation and frowned on the construction of new schools within three miles of existing ones. Increased interest in education at all levels produced an ever-expanding enrollment, which grew from 62,327 in 1885 to 119,593 in 1902. But despite the improvements and the continuous enrollment increases, the state continued to remain behind other states in average daily attendance and in the length of school terms. Educational advances continued to be made in Hernando during the remainder of the 1890’s. Although teachers were scarce in 1894, perhaps due to the revoking of certificates, finances improved. A list of accomplishments included the construction of new schools and the repair of old ones, a circulating library plan, a uniform course of study, quarterly written examinations for students, and the organization of reading clubs during the summer vacation. The county superintendent’s report for 1896 reported an accelerated interest in education throughout the county, but that the freeze of 1894-95 had cut into attendance as children were now required to work longer periods in the fields to help their families make ends meet. He stipulated that the county was well supplied with buildings, having built two and purchased one in the last two years. Cisterns had been constructed and wells dug for the schools, but patent desks were being utilized in only three. Whereas white teachers were passing the state required competency exams, Black teachers were not. Stoves had been placed in all schools and one-fifth of them had fences. The county had one advanced grade school at Spring Lake and a high school at Brooksville, while the remainder were grammar schools. Three-fourths of the teachers were natives of the county. Basically, a general term of four months was still followed, except where special tax districts provided from five to eight months of schooling. Hernando High School’s first graduating class in 1892 was composed of Hardy Croom and Mrs. Alda Burns Wright. They were followed one year later by Miss Louise Walker, Miss M. Walker, Miss E. Wilson, Miss Lola Bell, and Miss N. Thomason. As the number of graduates increased, Professor J. T. Mallicoat, principal of the high school from 1890 to 1896, suggested that an alumni association be inaugurated as a means of “keeping in touch.” But it was not until March 1899, that an organization calling itself the Alumni Association of Hernando High School initiated annual gatherings. The association met at the homes of members and various other locations up to 1931 when notations in the minutes’ book ceased for some undisclosed reason. Perhaps the Great Depression during this time made it difficult to finance the meetings, or perhaps interest had waned. In any event, no specific reason seems to exist for its demise. It is also interesting to note that no graduates were listed for the years 1897, 1900, 1904, 1905, and 1910. When Professor Mallicoat died in 1924, the association prepared a set of resolutions honoring his work.  The freeze of 1894-95 had struck the county’s economy a very hard blow, and with the drought of 1898, it caused the county to readjust teacher salaries. However, the county was able to build three frame schoolhouses, including a large two-story building, and it boasted that no old fashioned log cabin schools remained. Superintendent A. M. C. Russell reported in 1898 that:

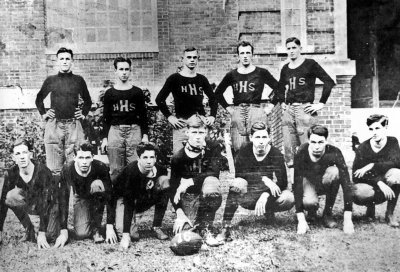

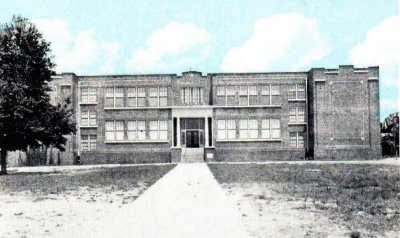

The county superintendent’s report for 1900 stated that four additional schools had been built and three cisterns constructed. Two of the schools, including the high school, had been painted. A general library and a museum of Florida curiosities had been added to the high school. By then, the number of schools had stabilized at twenty-four. White schools, numbering eighteen, were located at: Hammock Hills, Lake Lindsey, Istachatta, Rock Hill, Providence, Oriole, Ayers, Irwin Lakes, Cedar Tree, Sicily, Rural, New Harmony (Garden Grove), Spring Lake, Bay City, Riverland, Kayton, Withlacoochee, and Brooksville. Black schools, six in number, were located at: Brooksville, Mundon Hill, Hannibal, Bay Springs, Blue Sink, and Wiscon.  From Images of America: Brooksville by Robert G. Martinez Hernando High School in 1900 was administered by Principal I. B. Turnley, who was considered very resolute by at least one of his students, Edwin R. Russell. Getting to and from school then was becoming more of a chore as the hub of Brooksville shifted to the vicinity of the courthouse. The students took their lunches with them and ate under the trees at lunch time. The play area at rear of the building was divided by a stout wooden fence, with one side for girls and the other for boys. Water was obtained from a well, and carted into the classrooms each day where it was stored in large tanks. Subjects taught in the tenth grade included Latin, physical geography, trigonometry, botany and psychology. The commencement exercises for he class of 1902 listed the names of Miss Alice M. Hale, Miss Nell J. Coogler, Miss Hattie V. Rice, and Adrian O. Coogler as graduates and was held at Jennings Hall in Brooksville on April 25, 1902. The address was given and diplomas handed out by Governor, William S. Jennings, Hernando County’s most noted resident. The faculty at that time comprised: E. F. Wilson, Principal; Norton Keathley, Assistant Principal; and Misses Laue E. Sewell, Leda B. Kirk, Minnie H. Coogler, and Ira T. Sewell, teachers. The county’s recovery from the division of 1887, and from the economic disasters of the 1890’s was slow, but during the first two decades of the twentieth century it experienced advances in several areas including that of education. A constant rise in population from 2,476 in 1890 to 3,638 in 1900 and 4,997 in 1910 produced a requirement for more and better schools. Consequently, although one school was burned (an ever-present threat in those days of frame structures), three new ones were built during the early 1900’s. It was also at that time that Hernando High School and the Rural Graded School at Spring Lake were approved for state maintenance. By 1906, finances had improved to the point where an attempt was made to extend the school term to eight months for all white schools and to six months for Black schools. Hernando High School then had an enrollment of 146, with the school at Lake Lindsey having 81 students. Additional schools were opened at Aripeka, Stafford Prairie, and Bay City. The report for 1908 confirmed the county’s success with the eight-month term and stated that all school buildings had been ceiled. All schools had water facilities, and some even had organs. Teachers with first rate certificates and three years experience were receiving not less than fifty dollars a month, while the highest paid teacher in the county was getting $125. However, the frame high school building, then almost twenty years old, was deteriorating and in a sad state of repair. The decision was made to replace it with a brick structure with construction to begin in 1910. When completed, the new school would replace the old wooden building with five rooms and would include nine rooms at a cost of $10,000. In addition, running water was to be installed along with a pump house and a new well. By 1910, the county had twenty-two rural schools and two in Brooksville. Employed were thirty-six teachers. Eleven school districts had been designated, ten of which assessed a special school tax of three mills. The high school was then under the direction of Professor Wilder, who had six assistants. Although the brick high school was just a few years old in 1914, it was already overcrowded. This was due primarily to the fact that it housed all grades from first through the tenth. The high school students, numbering sixty-five, were crammed into two small rooms. So great was the crush that the Brooksville Christian Church had to be rented for two of the lower grades. Members of the senior class in 1914 were: Jennie Grozier, Beryl Russell, Willah Burrows, Imo Chambers, Myrtle Taylor, and Marion Watson.41  From Images of America: Brooksville by Robert G. Martinez Although space may have been a problem in 1914 it became acute in 1918, when Hernando High School burned under mysterious circumstances. Leamon Varn later recalled that a large delegation of Brooksville’s citizens turned out in a vain attempt to save the building. But modern fire equipment was lacking, and it was destroyed, with only some furniture and few educational materials being saved. Students were then housed for the next few months at numerous locations in the city: high school classes were held in the courthouse, with the eighth grade in Masonic Hall, fourth grade in city hall, the first and second grades in the Presbyterian Church, with still others in various places including the Christian Church, the Jennings Building, and over the Hernando State Bank. A positive result of the fire, however, was the construction of a more centrally located facility on Howell Avenue on property purchased from Mrs. Gary. By late 1919 or early 1920, the new school was ready for occupancy. It contained eleven recitation rooms, a library, several bookrooms, an auditorium, and a large basement. Members of the first class to graduate from there in 1920 were: Margaret Bell, Herbert Brown, Lula Hope and Marguerita Shaner. Other than the new high school, the only building to be remodeled was at Spring Lake, where four rooms, an auditorium, and some book and library space were added at a cost of $10,000.  From Images of America: Brooksville by Robert G. Martinez The destructive fire of 1918 did not prevent Hernando High from fielding its first football team that year. A picture of the team depicts the members as having little or no modern padding and no helmets. One of the players, Alan Hawkins, also was a coach. Although the won-loss record was not revealed, the team was supposed to have beaten a team from Hillsborough County. For some unknown reason no teams apparently were fielded between 1918 and 1923 Another team, coached by a Mr. Haines, appeared in 1923-24. The sports program was enlarged in 1925-26 with the addition of basketball, and in 1926-27 a baseball team was started. Both of these sports were coached by Mr. Duval.  The extension of Florida’s real estate explosion to Hernando County in the mid 1920’s placed a substantial burden on its educational facilities, especially in Brooksville where the Howell Avenue School was soon bursting at the seams. By 1925, it had an enrollment of 500, whereas, it had been constructed to accommodate only 350. Single desks being used by two students and other similar inconveniences were a daily occurrence. Although originally built on the supposition that it would last ten years, it was evident by then that a separate high school would have to be erected. A petition making that suggestion and authorizing a bond issue for that purpose was circulated about the county. But it was discovered that the bonding method would take some time to accomplish and circumstances dictated a shortcut. It was therefore suggested that the $75,000 needed for construction be borrowed, the only contingency being that the state legislature would have to grant the approval of such action. While a bill of authorization was being composed, construction plans encompassing the erection of a building containing ten recitation rooms, a study hall, and a gymnasium were delivered to the school board. If the state approved the financing the structure could be ready by the fall of 1925. While waiting for the legislature to act, the board examined several architects before selecting Frank F. Jonsberg on March 19, 1925. He was well known for his design of the St. Petersburg Junior High School and that of several other impressive educational buildings. Thus by the time the legislature approved the project many details concerning the building had already been worked out. Aside from the money borrowed to construct the new high school, the county school budget for 1925-26 totaled only $35,583.50. It included $6,000 for outstanding warrants, $350 for insurance, $550 for incidentals, $400 for furniture and apparatus, $150 for rent of classroom space, $720 for janitorial service, $1,500 for transportation of students, $500 for accounting services, $2,100 for the superintendent’s salary, $400 for board per diem and mileage, $286 for incidental expenses, $350 for printing, and $22,177.50 for teacher salaries. The total was $3,000 less than it would have been, because the legislature finally passed a statute providing free textbooks on a statewide basis for grades one through six. Thus the county no longer had to bear the expense for that item, as it had since 1891. The timely action by the board in providing for a new high school was borne out in the fall of 1925, when an expected enrollment of 550 for Brooksville schools topped out at 647. The term had to be delayed until the high school was ready for occupancy on October 5. When it opened, it also contained two overflow grammar school classes. An old house on its grounds also had to be pressed into temporary use. Several educational advances were begun in the county during 1926. One of the most important was the extension of the school term from eight to nine months. The additional month placed secondary education in the county on a par with most other high schools in the state and satisfied the term requirements of the Southern Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges. With that change and the adoption by the board of the six, three, three system with the start of a junior high, it was hoped that the high school would receive the accreditation of the Southern Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges to go along with the state accreditation which it had received some time ago. Another innovation that year was the founding of the Brooksville Parent-Teachers Association on August 11, 1926. Charter officers were Mrs. C. H. McLeod, President; Mrs. W. R. Ayers, First Vice-President; Mrs. George Turner, Second Vice-president; Miss Norma Burdin, Secretary; and Mrs. W. E. Oxley, Treasurer. Under its sponsorship a hot lunch program was instituted at the grammar school in January 1927, with Mrs. J. Hancock in charge of arrangements. It served 50 to 100 children in a remodeled building which formerly housed the janitor. Although aimed primarily at the undernourished and poor, it provided a service to all grammar school students for a number of years. Other improvements supplied by the association for the grammar school included library books and drinking fountains in 1927-28, shrubs for the grounds in 1928-29, and shades and pencil sharpeners for all classrooms in 1929-30. A third improvement was the construction of a new school at Masaryktown. That community had undergone a rapid expansion since its founding the year before, and was in immediate need of a school facility by 1926. To that end, a delegation of residents appeared before the county school board in May. Perhaps to express the seriousness of their situation, or to gain the attention of the board, it offered to pay half the cost of the building, becoming the first group to make such an offer. No definite action was taken by the board at that time, but at a later date permission was granted to build the school. Events moved swiftly, and by August ground had been broken for it. The site, plus $15,000 toward its construction, had been donated by the Hernando Plantation Company, developers of Masaryktown. John Ravos, manager of the Company, was named as its first superintendent. When it opened in October 1926, forty-five pupils, five more than was expected, enrolled at what was then proclaimed as one of the best schools in the state. Besides constructing a new school at Masaryktown, the county in 1926 was engaged in a general renovation of its schools with those at Croom, Hebron, and Stafford receiving $3,000 worth of repairs and another school being constructed at Spring Lake. Despite the additions, Brooksville schools were again experiencing large enrollments with the registration of 696 students. The problem was so acute at the grammar school that students had to be housed in temporary outdoor classrooms. And at Annuttulagga Hammock, a $30,000 bond issue was considered for the construction of two new schools. But the building expenses placed a financial burden on the school board, and in 1927 it was forced to appeal to the residents of the county to pay their taxes in order that the schools could finish out their terms. The board stated that keeping the full term was especially important since the schools had just recently been accredited by the Southern Association. A delay in tax payments could also prevent the opening of schools the following September. Complicating the financial picture was a record pre-school registration which closed at 1,119 students in June 1927. About 700 students were expected to attend schools in Brooksville, including 300 at the high school, while 500 would attend the other schools in the county. Of the seven Black schools in the county only the Mobley school was ready for occupancy. The main reason for residents falling behind on their tax payments was due to the collapse of the Florida real estate boom and was only suggestive of the financial problems soon to hit the county. Although hard times were just around the corner, educationally, the people of Hernando were looking forward to bigger and better things by 1929. The high school had been visited recently by the Southern Association and had received a rating of excellent. It was providing the students with three specific courses of study: General, Business, and College Preparatory, and was staffed by nine degree-bearing teachers. Enrollment in the fall of that year was 155, almost equaling the record year of 1926. But then, with the economic depression, the bottom dropped out of everything in l930. Schools opened as usual in September of 1930, but within two months the school board announced that it would be unable to keep the schools open for nine months and asked the parents of students attending high school if they could pay a tuition fee of $1.50 a month. It would allow the school to remain open for the full term thereby saving its accreditation status. But few parents came forward with any money and in February 1931 the board stated that most county schools would close, after only six months of operation, with the high school closing after seven, and with only two, Croom and Istachatta, running for the full nine. The reason for the reduced terms was that only 15 percent of the school taxes had been collected at that time. The Parent-Teachers Association sponsored a drive to raise money to keep the schools open for the regulation time, but only 30 percent of the grammar school parents promised to contribute. Fortunately some tax money did become available, enabling the board to keep the schools open for at least eight months. But even so, the Parent-Teachers Association and other groups were called upon to provide extra funds. The story was repeated in the fall of 1931, when County Superintendent J. B. Turnley remarked that it probably would be many years before the county could return to the nine-month term. Although the county was to receive $32,000 from the state for education expenses, twice the amount of the previous year, outstanding debts would consume much of that amount. Finances grew worse instead of better, and in early October the board declared that teachers would receive only 40 percent of that month’s salary. When November arrived, teachers were met with the announcement that they could expect to receive only one more pay between then and Christmas. No improvement came with the New Year, despite the fact that the board received $6,000 from the state in March 1932. As in the earlier instance, it went to pay off debts, and after squeezing out a month’s pay for teachers, it still left them one month in arrears. Eventually the board was reduced to paying teachers one-half a month’s pay for one month’s work; but by the end of the school year, it was still two and one-half months behind. By 1931-32, Hernando and other Florida counties which were in a similar financial plight were looking to Tallahassee for aid. But tax money was coming into state coffers just as slowly as it was into the counties’. Governor Doyle E. Carlton, who had come into office in 1929, looking to hold the line on taxes and spending, was then faced with the dilemma of keeping his promise or watching the state’s education system dissolve. One untapped source of funds was that which could be obtained by taxing parimutuel wagering at horse and dog tracks. The fight to legalize betting dated back to 1925, when racing began at Hialeah, but had met with little success until 1931. Using the leverage produced by economic conditions, sponsors of a bill making betting legal inserted a provision providing that one-half of the taxes collected would be distributed equally among the counties. The bill’s passage was thus assured. It was an immediate revenue producer with $737,301 in taxes resulting the first year, rising to $4,392,862 by World War II, and then to $25,000,000 by 1957. When Hernando County received its share of the race track funds in 1932, the school board sought to obtain its portion from the county commissioners. But the commissioners, who expected to receive about $9,000, were reluctant to discuss the matter and postponed any action on it. The school board was thereby forced to seek a bank loan to pay the teachers and to pass a resolution permitting it to cut salaries at any time during the next year. The educational picture became darker still when it was learned that the board would receive $50,000 less from the state in the coming year than was promised. It seemed the state had appropriated $7,500,000 for educational aid in 1931, but a tax shortfall had resulted only in a sum of $5,622,000. Tallahassee suggested that positions be eliminated for a period of time, and that activities of a questionable nature be curtailed. County schools opened in the fall of 1932 based upon a reduced budget. By cutting salaries and reducing administrative services, the budget had been cut back from $60,000 during the previous year to just $47,000 for 1932-33. In October, the county received enough state aid to pay 40 percent of the salary owed teachers for the month of September. The race track funds did little to ease the salary situation in the spring of 1933, because the school board was given only $2,000 of the $10,000 the county received. It had asked for two and one-half times the amount it was allocated. Therefore, to no one’s surprise, the teachers were once again months behind in receiving their pay. The stressful economic situation did not prevent the opening of the Brooksville Business College on December 12, 1932. It was located in leased quarters above Rogers Department Store. Supervised by H. D. Hall, it began auspiciously with fifteen the first session followed by twenty students in the next. It continued to advertise and, to presumably function well into 1933, but gradually dropped from sight. The result did not dissuade Clyde H. Lockhard from forming the Hernando Business College in August 1933. Lockhart, along with T. S. Rice and Mrs. Lucile Moore, opened the college in the fall in Brooksville’s new Murphy Building. But it, too, was unable to continue for any length of time. Apparently, Hernando was just not able to support such an institution during this difficult economic period. Failure of the business colleges was understandable especially when considering the continuous deterioration of public education. In June 1933, the school board cut teacher salaries by 25 percent and threatened once again to close the schools when the money ran out. When school opened that fall, it was expected that the term would end in four or five months. It was even suggested by the superintendent that Brooksville merchants initiate a voluntary sales tax with the proceeds to go to the schools such as was being done at Winter Haven. It became increasingly more difficult to collect taxes; declining from $11,316.83 collected in 1929 to only $4,863.15 in 1932-33. A new law designed to help financially beleaguered school systems permitted taxpayers to pay only that portion of taxes which would go to public education. Yet taxes remained unpaid, and by early 1934 Hernando schools were again in dire straits, with that year’s taxes going to pay teachers for their last year’s salary. As the Depression deepened across the United States, governments at all levels began to seek additional methods of getting the economy going and to especially provide support for sagging educational systems. Greater assistance for education was one of the campaign promises of David Sholtz when he ran for the governorship of Florida in 1932. He urged a return to the nine-month school term and for full pay for all teachers. Upon his election, he supported the inclusion of $312,408 in the State Superintendent’s budget for 1933 to be doled out to the counties to enable them to pay back teacher salaries. But even that extra sum was not enough to solve the financial crisis, and it was not until the Federal government stepped in that effective relief was forthcoming It came in the form of Federal grants of $610,21082 to fifty-five Florida counties, including Hernando, and namely through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration which was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal Programs. The promise of those Federal funds saved Hernando’s schools from closing in March 1934. Federal relief had come just in time to avert educational disaster in the county, but the struggle was far from over. Brooksville citizens organized a league for the purpose of advancing the cause to increase tax money for schools in May 1934. The League for Better Schools, as it was termed, sought to divert three-fourths of a cent of the gasoline tax, which was going for road construction, to education. It was headed by W. F. Ward, President; K. B. Hait, Vice-President and Mrs. Alice C. Hawkins, Secretary. By the time the league was formed, however, the weight of Federal assistance was beginning to be felt in the county. Officials from the Civil Works Administrative, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and the Public Works Administration inspected county school facilities during the summer of 1934. They found white school buildings to be adequate but Black families to be almost non-existent. The only Black school found in the county was located at Brooksville Throughout the rest of the county, Blacks were being educated in homes, churches, and other places. The agencies proceeded to assist the county in upgrading Black education by constructing a two-teacher Black school at Mundon Hill, and another in Brooksville on land donated by P. H. Grelle. The latter was a six-room building large enough to accommodate all of the city’s Black students. Consolidation of white schools was aided by construction of a school facility at Lake Lindsey, which permitted the combining of the Hebron and Stafford schools. The practice of cutting the school term short caught up with Hernando High School in 1934, when the Southern Association threatened to disaccredit it. Most other counties in Florida had managed to keep the nine month term for their high schools, there being only 9 out of 125 institutions which had to resort to shorter terms. County educational finances received a welcomed boost in the spring of 1935 when the state passed a law providing free textbooks for the upper six grades, as it had for the lower six back in 1926. Whether due to that circumstance, or to the threat of disaccreditation, the county budgeted for a nine month school term at Hernando High in August 1935. But the regular term could not be sustained, as it was cut to eight months again in 1938, thereby causing the high school to lose accreditation. State and Federal activities directed toward improving the quality of education in the county were progressing as the 1930’s drew to a close. Although finances were still tight, new schools had been constructed around the county, including a four-room brick veneer school at Lake Lindsey, where three teachers supervised sixty pupils in grades one through eight. The school budget was also on the increase, reaching a record high of $85,843 in 1938-39. The outbreak of World War II temporarily reduced student enrollment, especially by the 1942-43 term, but educational improvement continued. The reduction in the number of students caused the closing of some small rural schools such as at Aripeka. The student population was then bussed to schools in Pasco County.  Soon more teachers than ever before were being certified. A survey revealed that thirty-nine had B.A. degrees, while 32 percent and 29 percent had two to four years of college and less than two years, respectively. By 1944, the county was in the best financial shape it had been in for a long period of time, with all outstanding debts paid except for annual dues on educational bonds. In fact, the budget was so solid that the school term was restored to nine months and accreditation was again sought from the Southern Association. After World War II, the county’s main effort centered on school consolidation and, on further improving the financial resources to enable the system to cope with the influx of students which was soon to materialize when prosperity returned. Consolidation permitted the system to provide a higher quality educational experience for students and eliminated duplication of facilities. It was suggested that three white schools could cover the educational needs of the entire county. Students living near the Brooksville area would be brought there for schooling, while the Hammock and Istachatta schools would be merged with Lake Lindsey, and too, the Garden Grove and Masaryktown schools would be merged with the Spring Lake School. In the eastern and southwestern sections of the county, the Richloam and Aripeka schools had already been closed. To finance the change, the school board again sought to increase its portion of the racetrack revenue it was receiving from the county. It was successful in introducing, and having passed a bill to force the county to grant one-half of the funds received to the schools. The importance of the result became clear when an analysis of the track income showed that county receipts had risen from $9,226 in 1932-33 to $98,000 in 1945-46, and that of the $531,000 obtained during those years, the schools had been given only $51,654, while the road and bridge fund alone had received $177,044.77 The need for higher teacher salaries and the increased expense of education was reflected in the school budget for 1947-48, which was set at over $100,000. It included a 45 percent raise for teachers. When the school board attempted to follow the consolidation plan it had developed, it ran into bitter opposition from parents in rural areas who refused to send their children to Brooksville or to other schools located some distance away. The conflict was partly resolved by allowing the Hebron school to exist as an isolated district until suitable roads would allow suitable transportation to Brooksville. The Garden Grove school was merged with Brooksville, Crooms’ Black school with Moton (Brooksville’s Black school), and somewhat later Istachatta was merged with Lake Lindsey. By 1948, the county had reduced the educational facilities to just six elementary and two secondary schools serving 1,259 students. If school authorities were content with those results, they were doubly pleased the next year, when Hernando High School was finally reaccredited by the Southern Association.  As the county continued to expand educational facilities in the 1950’s to meet increasing enrollments, the school budget rose accordingly, hitting a postwar high of $424,738.93 in 1952-53. By then, further consolidation had reduced the total number of schools in the county to only six. Student population numbered 320 at Hernando High, 569 at Brooksville Elementary School, 61 at Spring Lake, 62 at Lake Lindsey, 341 at Moton and 26 at Bay Springs. As the enrollment increased, so also did the teacher salaries and the number of new additions to old buildings. The basic starting salary rose to $3,400 in 1957, with almost as much money going into salaries as composed the total budget in 1952. In the fall of 1957, the state recommended a $1.1 million construction program be initiated by the county. It had been determined that Hernando County would need twenty new classrooms in the next five years to keep pace with student growth. Construction of a new high school and a new elementary school were included in the recommendation. During that period, the county embarked upon an unprecedented expansion in physical facilities by purchasing a large tract of land at the north end of Bell Avenue from J. C. Emerson. On this site was constructed a comprehensive high school facility which has since been enlarged almost on an annual basis. Early in the 1960’s, the school budget edged over the $1,000,000 mark to reach a new high of $1,500,000 in 1965. It was difficult to believe that just thirty years before, the budget had totaled $40,000. School consolidation continued during the 1960’s with the closing of the Spring Lake and Lake Lindsey schools and, with integration, the gradual phasing out of Moton High School. Other changes which took place included the razing of the old grammar school on Howell Avenue, the expansion of the primary school to twenty-four rooms, the razing of the old high school on Bell Avenue, the construction of a $300,000 junior high adjacent to the site of the new Hernando High School, and the purchase of the Catholic school property located on Highway U.S. 41 North. The cost of operating these new facilities raised the school budget past the $2,000,000 mark in the late 1960’s, with almost half of it coming from state funds and another one-fourth coming from the Federal government. Between 1960 and 1975, the county population rose from approximately 11,000 to an estimated 30,000. During that time, the school system constantly updated its physical facilities and increased its budget to meet educational demands. By the early 1970’s the school system was operating six campuses at various locations throughout the county, serving some 3,965 students and employing over 200 full time classroom teachers. The expense per pupil based on the average daily attendance for 1970-71 was $785.85. Instructional salaries for a ten month teaching assignment ranged from a minimum of $6,400 for Rank III to a maximum of $11,904 for Rank I in 1971. The Adult Education Center had an average enrollment of 5,000 full and part-time students in 1972. The dramatic population growth experienced by Hernando County in the late 1960’s ultimately spurred a movement to establish a post secondary institution within the county, with or without the cooperation of Pasco County. But before tracing the development of Pasco-Hernando Community College, let us examine the history of the junior college in Florida. The movement had been rather slow to develop in the State of Florida. A citizens committee on education was formed in 1947 to examine secondary and post secondary education in the state. After some detailed studies, the committee recommended that junior colleges be located in major population centers with support to come from the state and the county or counties wherein they resided. But little activity in establishing them was noted until the formation of the Community College Council in 1955. The purpose of the council was to develop long-range plans and establish priorities for a junior college system. It proposed that the state be divided into twenty-eight districts with a college to be located in each. The method would place 95 percent of the people of the state within commuting distance of a two year college. The response was dramatic, and by 1964 nineteen districts were operating twenty-nine junior colleges (the number later being reduced with several Black colleges were phased out). During the next few years, the remainder of the districts added their colleges to the system until only one district comprising Hernando and Pasco Counties lacked such an institution. The effort to seek a junior college for Hernando County began in late 1966 when County School Superintendent John W. Hull approached his counterpart, Chester Taylor, in Pasco County. It had been determined that it would have to be a two county program, as neither one was developed enough to support a program by itself. At that time, Taylor told Hull that he felt his county was not ready to support a college. Despite the rather cool reception, Hull still wished to establish an institution of higher learning in his county and made ready to get things rolling so that an application might be submitted to the state in 1967. Hull was finally able to get the Pasco County School Board interested in at least making a survey to establish the feasibility of starting a junior college. But a major problem arose concerning just where the facility would be placed. It needed to be relatively close to the Hernando County line, for it was conceded that it would have to be erected in more populous Pasco, so as to be accessible to Hernando residents. Possible locations mentioned at that early date included: Gowers Corners, Spring Hill, or the old mental hospital site on State Highway 98 north, which had been set aside by the state several years before. The earliest time considered for the opening of a college was the fall of 1969. A survey determined that a college could be supported by the counties, if they were willing to pay the price. It was estimated that the expense to Hernando would be $13,000 and to Pasco $50,000, with additional funds for operation coming from the state. By mid April 1967, the counties were near to selecting a campus site. A sum of $1,000,000 was mentioned as that required to establish the first building. College personnel would include a president, a couple of counselors, and thirty instructors. It was expected that 350 full time students and 410 part-time students would comprise the student body in the first year. The boards established an interim committee to look into the venture. The distinct possibility of at last getting the project off the ground produced an offer of a campus site from the Mackle Brothers, developers of Spring Hill. They were willing to donate a 400-acre parcel of land for the campus located opposite their development on state highway 19. The offer even included the running of sewer and gas lines to the site at no charge. Although the gift was considered, the Hernando County Board of Education agreed that the campus would have to be located in Pasco County, as the latter was larger in population and would be contributing three times as much money to the institution. The decision was then made to place the college in north Pasco within fifteen to twenty miles of Brooksville. The location problem solved, the legislative delegates from the two county area were requested to obtain planning money from the legislature. Representative Tom Stevens of Pasco County was able to accomplish this at the last minute of the 1967 session. The $30,000 which was authorized was used over the next two years to further the organization of the college. An additional fund of $50,000 was approved by the legislature for the same purpose in 1969. Dr. Lee Henderson, State Director of the Division of Community Colleges, discussed the problems of establishing the college with the Hernando and Pasco County School Boards at a combined meeting in October 1969. The combined boards wanted to place the college at Gowers Comers, but Henderson suggested that it be located near a town where water and sewer systems could be readily provided. However, no decision was made in establishing a site, so the date of getting the college started was pushed back to September 1971. Another meeting was later held, but still the site problem could not be resolved. The Gowers Corners location was motioned but not seconded. The Pasco delegation was split with two members designating a New Port Richey location, one a Land O’ Lakes site, one a Dade City site, and two for a Hernando site. If a decision could not be reached, it was thought the college might be canceled by the state. Hernando citizens became critical of the foot dragging by Pasco’s board, and a statement was made that Hernando should go it alone rather than lose the college altogether. As if to solidify that fact, Miss Jean Truitt of Brooksville offered 100 acres of land on the truck by-pass off U.S. 41 as a site to the Hernando County School Board. The combined school boards met in January 1970 to examine the Gowers Corners, the truck by-pass, and the St. Leo Abbey sites as possible locations for the college. Eight board members appeared to like the Gowers Corners site best. The question finally appeared resolved when that location was picked at the next monthly meeting. The site question had not been resolved, however, and the controversy of where to place the college continued on until the Pasco School Board selected a location on State Highway 41 north in June 1971. Following that selection, the school boards of the two counties submitted prospective names of college trustees to Governor Reuben Askew. The College Board of Trustees was formed in December 1971, with the following members from Pasco County: Scott Jordan, Grace P. Hall, S. C. Bexley, Jr., Dr. Marcelino Oliva, Jr., and Wayne L. Cobb, and the following from Hernando County: Earl Patterson, Winslow Brewer, Dr. Gerald W. Springstead, and James H. Kimbrough. The first duty of the board was the selection of a president for the college, which it fulfilled in March 1972, when it chose Dr. Milton O. Jones of Clearwater. The college board agreed during their many months of discussion to support three college centers, placing one in Brooksville and New Port Richey to go with the one slated for Dade City. Dr. Robert W. Westrick of Jacksonville was chosen to head the Brooksville Division of the college in April. Local response to the opening of Pasco-Hernando Community College’s Brooksville Division was overwhelming, with 175 students enrolling in September 1972. Phenomenal growth of the college resulted in 237 students attending the Brooksville center in 1973-74, 325 in 1974-75 and 569 as of November 7, 1975. |