Energy & Marine Center

Pasco County Schools, Port Richey, FL

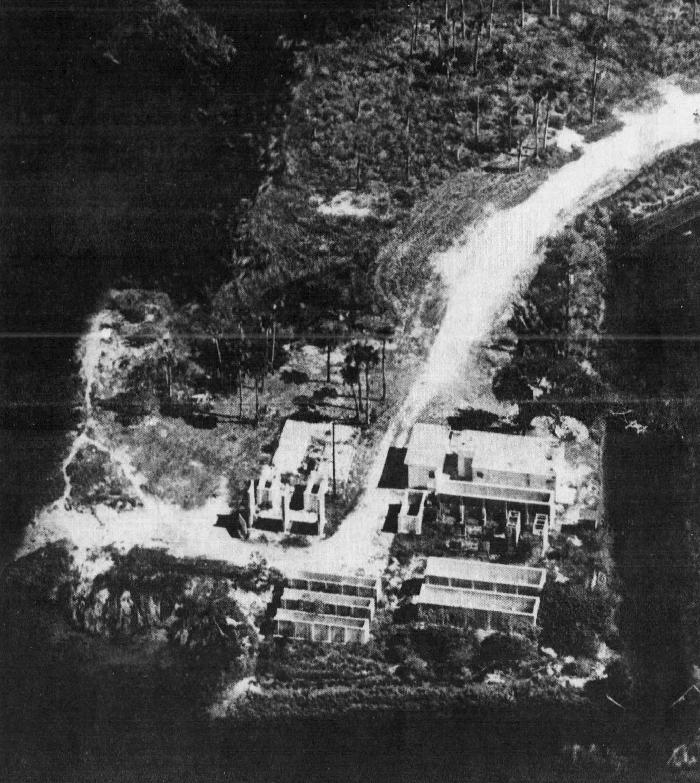

Located on ten acres at the north end of Old Post Road in Port Richey, Pasco County School’s Energy & Marine Center (EMC) is situated on a coastal hammock on the Salt Springs Run estuary bordered by Werner-Boyce Salt Springs State Park. The parcel includes several mangrove islands.

Founded in 1975, and originally known as the “Energy Management Center”, a full history of the EMC requires that we go back a bit further in time. Up through the 1940s, this area was virtually untouched by civilization. Life-long resident and historian Terry Kline says that he and his friends had a campsite there in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The future of the site would be forever changed with the help of a man named Newt Gehring, who lived in Pinellas County. He fancied himself to be a scientist and inventor, even though he had no formal education in those fields. In April of 1962, the St. Petersburg Times published an article about his latest venture. He claimed to be able to convert salt water into potable drinking water, along with numerous other chemicals, through a “secret” process he developed called “electro-dialysis”.

In January of 1962, Mr. Gehring created a corporation named Ocean Resources, Inc. to put his plan into action. Local stockholders bought into his idea of a de-salinization plant in Port Richey along the banks of Salt Spring Run – allowing Newt to raise $50,000 to get things off the ground. A business office was established on West Main Street in New Port Richey in the rear of William Grey’s real estate office.

Officers of the corporation were Newt Gehring as president, New Port Richey attorney Sam Y. Allgood as secretary, St. Petersburg engineer John M. Zobec as treasurer and plant manager, First National Bank of New Port Richey president Richard A. Cooper as assistant treasurer, Morris Erickson of Largo as assistant secretary, and vice-presidents H.A. Summers, Richard Schoenbaum, Anthony P. Coryn, and Pauline Gehring (Newt’s sister).

Ocean Resources, Inc. purchased the 10 acre parcel and began work building the de-salinization plant. Gehring claimed the plant would process up to 50,000 gallons of salt water every day – turning it into 40,000 gallons of fresh drinkable water, along with various chemicals. They had no idea what they were going to do with the fresh water, and planned on concentrating on generation of the chemicals, which they said would generate a good deal of revenue. Mr. Gehring said he could extract 34 different chemicals from the sea water, including potassium, calcium, sulphur, sodium, chlorine and magnesium. Des Little Paving Company would be digging a small inlet canal on the south side of the property, as well as filling low areas, and building the access road. The plant was expected to be complete and operational within two months.

Newt Gehring was an ambitious man who believed in his ideas. As a side note, it is also worth mentioning that he developed a similar process using “ionic-dialysis” to process waste in a sewage treatment plant. He sold this idea to the city of Madeira Beach in Pinellas County in 1968. This venture was also funded in large part by private investors who bought shares in his company.

By early 1970, things were beginning to fall apart for Newton Gehring. As it turned out, even though his “secret” processes could be demonstrated to work in his garage laboratory, they were never commercially feasible for large operations. The Madeira Beach sewage treatment idea came tumbling down when the city discontinued attempts to use the new process in 1969, claiming it didn’t work. Newt was sued by shareholders. In January of 1970, he was charged with 22 counts of violating state securities law. He was found guilty in November of 1970.

The de-salinization plant in Port Richey had ceased activity in the late 1960s and had fallen into disrepair by 1971 when shareholders insisted on answers. The plant had been vandalized and there was no sign of business activity. Even so, the laboratory and settling tanks were of concrete construction and remained intact. They would eventually be incorporated into the plans of the Energy Management Center when the Pasco School Board purchased the property several years later.

When the de-salinization plant was abandoned in the late 1960s, Ocean Resources, Inc. was dissolved, and the property sat vacant for several years. A short interim agreement was made with the Pasco County Mosquito Control District to use the holding tanks on the property for research purposes. They reportedly kept minnows in the tanks and fed them mosquito larvae.

Shortly after 1970, a marine science station was established in Crystal River for use by school students. Funded largely by grant money, it was operated as a multi-county facility. In 1972, Pasco County contributed $10,000 to the operation of the Crystal River Marine Science Station. But due to the problems of transporting students all the way to Citrus County, they decided not to participate in the program in the 1973-74 school year. Instead, they developed plans to create their own marine science center for Pasco County students.

On June 18, 1974, the Pasco County School Board purchased the ten acre de-salinization plant property from Ocean Resources, Inc. for $50,000. The grantors of the deed were the last board of directors of the previously dissolved corporation. They were Newton P. Gehring, Anthony E. Coryn, Harry A. Summers, Meredith Dobry, John Zobec, Richard Schoenbohm, William F. Baker and R.H. Francasio.

Plans for the new education center had to be slightly modified before they even got underway when it became clear that grant money for a marine science center was no longer available due to the previously established Crystal River Marine Science Station. Not discouraged, the Pasco County School Board, based on a suggestion from member Jay B. Starkey Jr., changed the focus of the planned center to be an energy management center. Instead of focusing primarily on marine science, it would be used to teach students about energy management and conservation. Now named the “Energy Management Center”, plans moved ahead with a planning grant of $46,172 from the Federal Education Act’s Title III funds.

By 1975 plans were essentially finalized for the new Energy Management Center at the site of the old de-salinization plant. With Dick Endress as a science coordinator, and Rose Fernandez as federal projects coordinator, federal grants were obtained totaling $225,000. Fourth and ninth grade students would receive nine weeks of classroom instruction coupled with trips to the energy center to do research and hands-on experiments.

During the first part of 1975, the five large holding tanks at the site were connected and fed with running seawater to hold marine specimens. A dock was built, and a boat was obtained for use by the center. An electric turbine was installed for generating electricity, and an observation deck and classrooms were built for students.

Thomas Baird was named project director of the Energy Management Center. A 1973 graduate of the University of South Florida with a masters degree in science education, he joined the Pasco County school district in August of 1974.

Much of the curriculum and day-to-day operation of the center was the responsibility of science teacher Mike Mullins. Ex-NASA astronaut Dr. Anthony J. Llewellyn, a faculty member of the Department of Energy Conservation and Mechanical Design at the University of South Florida College of Engineering was also brought on board to help with course planning. Teachers at the Center – in addition to Mike Mullins – were Kay Dacko and Dave Lawrence

In addition to energy management topics, students also had the opportunity to study marine life in a manner similar to instruction at the Crystal River marine center. By the beginning of school year 1975-76, nine Pasco County schools were participating in a nine-week course that involved classroom study along with three trips to the Energy Management Center. The schools were Bayonet Point and Gulf junior high schools, and Lacoochee, Cox, Cypress, Elfers, Zephyrhills, Northwest and Shady Hills elementary schools.

In addition to its main function of educating local students about energy conservation and management, the Energy Management Center was quickly building a nationwide reputation as a state-of-the-art energy science center. In January of 1976, it was host to a workshop conducted by Dr. King Kryger of the Interstate Energy Conservation Leadership of Denver, Colorado. Attendees at the conference were personnel from Pasco, Hillsborough, Citrus, Orange and Union Counties, St. Petersburg Junion College, the State Department of Education, the West Pasco Audubon Society and Florida Power Corporation.

In June of 1977, Rose Fernandez – supervisor of federal projects with the Pasco County school board – announced that the Energy Management Center was applying to be part of a Federal extension service program that would include centers in ten states. A Federal grant of $1.1 million dollars would be split between the different state energy centers. Unfortunately, Florida was not chosen to participate in this program. So the Energy Management Center had to face the possibility of obtaining other grants, or drawing money from the Pasco School board budget in order to continue operating. The center was now providing instruction to more than 3,000 students per year.

Upon losing the federal grant, the Pasco County School Board had no intention of letting the Energy Management Center go by the wayside. In fact, school board member Jay B. Starkey Jr. expressed concern that some county schools had not opted in to participate in programs at the center. The Board voted in favor of mandating that all schools in the county be included in programs at the Energy Management Center. Application was made for another federal grant to help finance the development of programs and curriculum. By the end of 1977, program director Thomas Baird announced that the Energy Management Center was producing printed material and lesson plans for teachers to use in the nine-week energy management course that would be taught at all county schools, and augmented by several trips to the center for hands-on student experiences.

Faced with the prospect of teaching all 4th and 9th grade students about energy management at the center, the logistics of such a program had to be faced by the school board. The current facilities could only accommodate 35 students at a time. And in order to handle all Pasco County students, it would need to double that capacity. With the expiration of any federal grants, the Pasco County School Board was now financing the operation of the center in full. So it became necessary to search for other funds.

In December of 1977, the efforts of Rose Fernandez to obtain another federal grant were beginning to pay off. It was announced that a team of experts from the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare in Washington, DC would travel to Pasco County to review the Energy Management Center and its operation. This opportunity came in part because the Florida Department of Education had recommended the Center to federal officials.

In January of 1978, the Energy Management Center was visited by the federal team of experts, and received accreditation from the U.S. Department of Education. This meant it was eligible for additional federal grant money. The Center would disseminate materials to other centers around the country, and Pasco County educators would travel to other states to help them set up their own centers based on the Pasco County Energy Management Center model. Science centers in other states also sent their representatives to Pasco County to tour the Energy Marine Center. One of these visits was from a team from Wichita, Kansas, looking for inspiration for what would become their new “Energy Adventure Center”.

With federal accreditation, money would also be available to help expand the Center to accommodate more Pasco County students. By now, the staff – still headed by Thomas Baird – consisted of eight people, including five instructors, a secretary and a maintenance man.

By April of 1978, plans were moving into high gear. The school board approved building a new classroom building at the Energy Management Center, and accepted a plan for the building from local architect Charles Sharrod Partin. It was a design based on the historic stilt fish camps that were built in the early 1900s offshore from Pasco County. Constructed of heavy timbers, the classroom building would be about 30 feet square, with tin roof, and a six foot deck on two sides extending to the existing observation tower. The area under the building could also be used as a sheltered class area. Built by Brooksville contractor John Grubbs, the cost for the new classroom building was $40,000.

By its fifth anniversary in 1979, the Energy Management Center had achieved widespread acclaim across the nation and at home. It had become a model for 17 other Florida school districts. Eight of those had started similar programs in 1978-79, and another nine were given federal grants to do the same thing in 1980, including Bay, Clay, Hendry, Hillsborough, Holmes, Okaloosa, Palm Beach and Polk counties. Federal grants to support the Center up through the end of 1979 totaled $689,000.

Funding for the Energy Management Center had become a constant challenge to administrators and the Pasco County School Board. However, given the importance of the programs taught at the Center, the school board eventually resolved to foot the cost themselves when that became necessary. Additional federal or state grants were used to spread the work about the Center to other local and national school districts. By 1981, all children from the county’s 4th, 5th, 6th and 8th grades were visiting the Center on field trips. This amounted to about 9,500 students. And the number was expected to rise beyond 11,000 in 1982. By its tenth anniversary in 1985, students from every science class from 4th through 12th grade were spending at least one day at the Energy Management Center.

In July of 1974, the Energy Management Center – now under the directorship of Terry Switzer – was named as the best in Florida for the school year 1983-84. The award was presented by the Florida Association of Science Teachers at its convention in Tallahassee.

Since its inception in 1974, the Energy Management Center had focused on a curriculum based around energy conservation and management. This was due in large part on the availability of federal grants for that purpose. But the original concept of a marine science center was never out of mind. The property location in a tidal estuary along the banks of Salt Springs Run provided ample opportunity to explore marine habitats and wildlife. Students at the Center were taught, and experimented with, a mixture of energy and marine topics. Finally, with less dependence on federal grant money, the idea was floated to rename the Center to something more appropriate to its actual academic programs.

At the Pasco County School Board meeting in April of 1988, it was decided to rename the center to the “Marine & Energy Center”. The decision was made in part based on suggestions from elementary school students.

In the fall of 1991, the Pasco County School Board was facing budget issues, and trying to figure out where money could be saved or which programs could be cut. The suggestion was floated that the Energy & Marine Center, now directed by Gary Perkins, might need to cut back its operations and personnel. Doing so would allow some of the EMC staff to be reassigned to normal classrooms instead of teaching at the Center. At that point, the EMC had ten employees and a budget of about $380,000 per year. The cost of busing students to the Center was also a consideration.

At the end of the 1991-92 school year the Energy & Marine Center was still threatened with budget cuts. Ironically, it was honored at the 1992 Governor’s Environmental Education Awards ceremony in Tallahassee as a finalist. But due to lack of funds, the EMC was not the thriving program it had previously been. The teaching staff had been reduced to five, including director Gary Perkins. The EMC teachers now only worked with 4th and 5th graders. And the budget, not including salaries, was only $35,000 per year. To make things even worse, a storm in 1993 caused about $100,000 worth of damage to some of the EMC buildings and its docks.

By 1996, budget constraints were still a big problem. But a little help came in the way of a grant of $20,000 from the Southwest Florida Water Management District. The funds allowed middle school students to visit the EMC for summer camp. It also made it possible for students in 5th through 8th grade to do field trips during the school year. One of the summer camp programs made available by the grant was the Salt Springs Run Estuary Adventures, called “SEA” for short. Another program, offered to kids between 4 and 6 years old and their parents, was named “Seaside Science”. By the end of 1996, the Energy & Marine Center only had two science teachers on staff – Ken Ford and Jean Knight.

Even though the Energy & Marine Center had fallen on hard times due to budget cuts, its recognition nationwide survived. It was noticed by Dr. Jane Goodall, world renowned biologist and primatologist, who brought her “North American Roots & Shoots” program to the EMC in October of 2000. It is a week long experience for teenagers, who were able to paddle using the EMC’s fleet of kayaks, to trawl offshore collecting plankton, and use a seine net to gather sea creatures. The program attracted participants from all over the United States and Canada.

By the summer of 2002, the programs of the Energy & Marine Center had been drastically scaled back – consisting only of summer camp activities. In order to help finance operations, students were charged $175 each to participate in one of the three one-week sessions called the “Summer Time Program”.

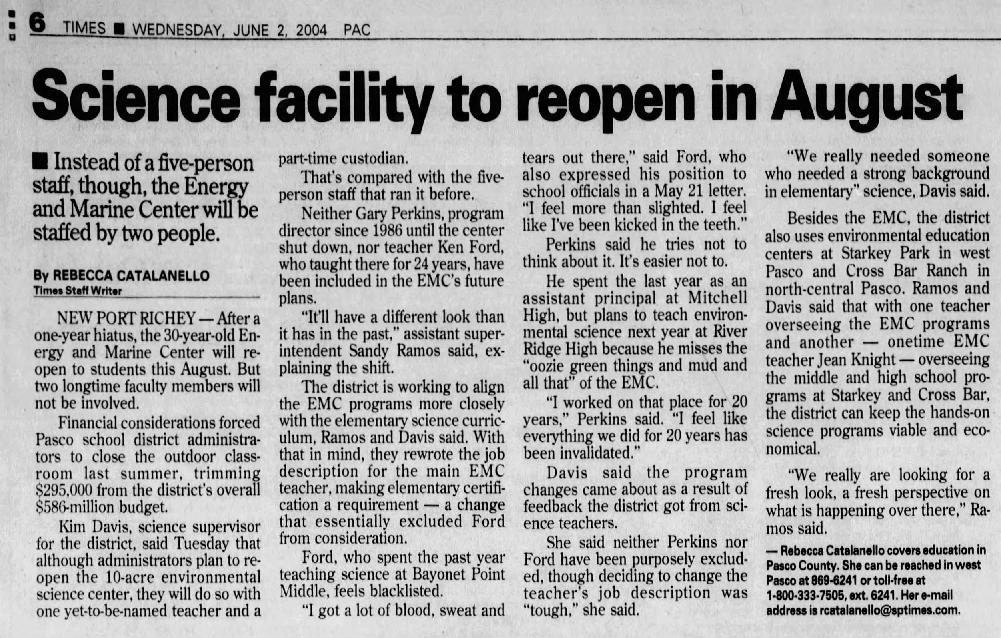

In 2003, another round of state budget cuts to the school system – to the tune of $10.3 million – resulted in the closure of the Energy & Marine Center. Thankfully, the closure was only temporary. And in August of 2004 the EMC was again opened for classroom visits and summer camps.

Although treated with some fanfare from parents, science teachers, and former students, opening of the EMC again was bittersweet. Instead of a staff of five people as before, the Center would only have a full time staff of one teacher and a custodian. Gary Perkins, who had been program director since 1986, and teacher Ken Ford, who had taught at the EMC for 24 years, did not return – although they did continue to be employed by the school district. Ford continued to teach science at Bayonet Point Middle School. And Perkins, who had been serving as assistant principal at Mitchell High School during the EMC closure, would continue to teach science at River Ridge High School.

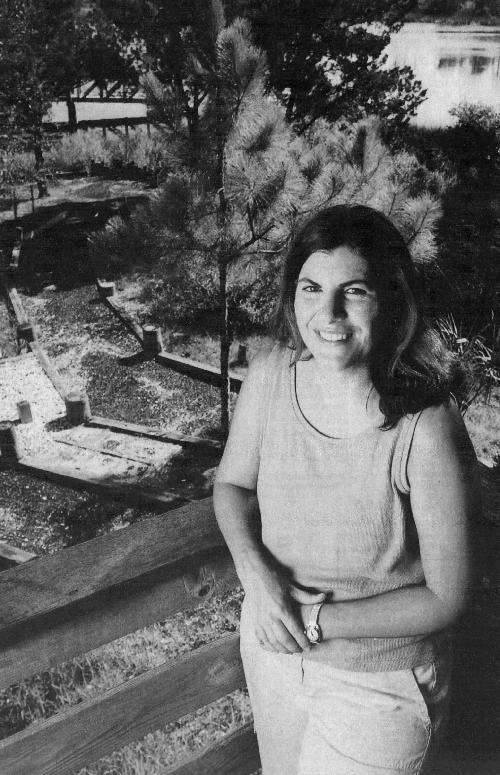

EMC director when it re-opened in 2004.

It was funding constraints that caused the workforce reduction at the EMC. But the reason given for not bringing back Perkins and Ford was that the School Board wanted to put more emphasis on elementary education. So they chose an elementary school teacher to provide leadership for the newly re-opened Energy & Marine Center. She was Donna Hoague. The custodian was Ray Rios.

Getting the EMC open again was something of a project in itself. There was a fair amount of maintenance work required. And a new curriculum was being crafted. Donna enlisted the help of Kim Davis, supervisor for curriculum and instructional services for the school district; and former EMC teacher Jean Knight, who was serving as an instructor at the Starkey Education Center in Starkey Park. The Energy & Marine Center was once again a venue where Pasco County students could learn about their environment and get hands-on experience.

In January of 2006, Joshua McCart joined the Energy & Marine Center staff as an environmental sciences teacher for high-school students.

In early 2009, the EMC was host – along with neighboring Werner-Boyce Salt Springs State Park – of the “Learning in Florida’s Environment” (“LIFE” for short) program offered by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. It kicked off with a pilot program offered to students from Chasco Middle School, and was expected to be extended to additional students over a 3-1/2 year period.

Also in 2009, the Energy & Marine Center benefited from a Federal Title I grant to support programs for low-income elementary and secondary students. Each school in the county sent 25 students to the programs, which were conducted at Crystal Springs Preserve and Cross Bar Ranch, as well as at the EMC. In all, the Pasco County School Board spent $35,000 to support the summer camp program. Federal Title I funding continued in subsequent years, and by 2011, Pasco students were also visiting Starkey Wilderness Park and the Florida Aquarium in Tampa as part of the summer camps, which were referred to as the “Pasco Environment Adventure Camp Experience”.

In the years since the Energy & Marine Center was re-opened in 2004, it has continued to grow and regain the reputation and recognition it had in the first 30 years of its existence. The curriculum, now centering almost exclusively on marine science, as had once been envisioned – has been expanded to once again include middle and high school students. By 2013, the EMC was playing host to field trips for 4th graders from 45 elementary schools, and 9th to 12th grade students from 12 different high schools. Full time EMC staff has remained minimal – since teachers from the schools sponsoring the field trips receive pre-trip instruction and training, and accompany their students to the Center.

As this article is written in 2025, the Pasco County Energy & Marine Center has managed to survive through many hard times, and has achieved its goal of educating students – and teachers – about energy management and marine science. It currently supports the “Marine Explorers Elementary Program” for 4th graders, and the “Eco-Research Program” for high school students.

Probably the best testament to its success over the years can be learned from the actual words of students it has taught …. “This is the best day I’ve ever had at school”, “I wish every day at school could be like this”.

This article was published 30 Mar 2025 by Paul Herman, digital media archivist, West Pasco Historical Society