HISTORY OF PASCO COUNTYThe President and the Abbot

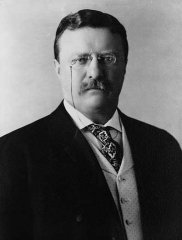

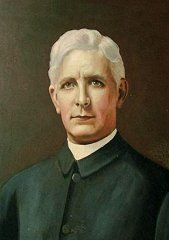

The following article was provided to this web site by Edward Herrmann. By JAMES C. HOGE In 1905 in Jacksonville, Florida, two men of divergent backgrounds met and there formed a warm friendship that spanned the rest of their lives. The date was October 25th; Abbot Charles Mohr of Saint Leo College and Abbey was in town to meet with State Senator James Taliaferro, of Tampa, and two others. At the meeting he learned President Theodore Roosevelt, in the first year of his second term of office, was in town and scheduled to speak that day at the Seminole Club of Jacksonville. Abbot Charles was easily persuaded to join the others of his group to hear the president speak. Abbot Charles and his party arrived at the Seminole Club prior to the president’s arrival and had the opportunity to meet with Governor Napoleon Broward of Florida and Mayor George M. Nolan of Jacksonville, among others. As soon as President Roosevelt entered the club and was ushered to his seat, Senator Taliaferro pushed toward the president’s chair, Abbot Charles in tow. President Roosevelt, his characteristic ebullient self, reacted to the introduction of Abbot Charles enthusiastically: “All my information about abbots comes from the novels of Sir Walter Scott. I am glad to shake hands with a real live Benedictine abbot!” The conversation continued at length as Abbot Charles referred to himself as a fellow federal officer of the U.S. government with sixteen years of service as postmaster of the township of Saint Leo. “I am delighted to have a Benedictine abbot as one of my co-laborers. I have the highest regard for your church. On my Cabinet as secretary of the Navy is a good Catholic, Mr. Bonaparte (ed. note: Charles Joseph Bonaparte). A few days ago I saw Cardinal Gibbons (ed. note: James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore); your church has nothing to fear from me.” Obviously pleased to have a genuine abbot in his company, the president invited Abbot Charles to sit near him on the balcony adjoining the speaker’s stand, which the delighted abbot proceeded to do as others pushed forward to greet the president. Abbot Charles was so ecstatic over his encounter with President Theodore Roosevelt that he sat down later in the day to write a five page letter to the monastic community, despite the fact that his trip continued on to Belmont Abbey, N.C., for a general chapter meeting of the abbots of the American Cassinese Congregation of the order. “The president (in his speech) speaks with the greatest clearness, ease and deliberation, but in conversation he stammers a bit. The cartoons we see of him are pretty true to life. He gesticulates much, and in speaking shows all his teeth.” He ended the letter, which was read at the monks’ supper upon receipt, with the closure. “I hope my community will keep the promise I made to the President, namely, that we will pray for him.” After his return to Saint Leo from his trip to Belmont, Abbot Charles wrote his first letter to President Roosevelt at the White House. No copy of it exists, but in the letter he extended to the president an open invitation to visit the college and abbey. Roosevelt never did, but replied with a similar invitation to Abbot Charles to visit the White House. This was not to be. However, soon after Roosevelt retired from office, Abbot Charles visited him at Roosevelt’s family home, Sagamore Hill, at Oyster Bay, Long Island, N.Y. Only in December, 1908, near the end of Roosevelt’s second term in the White House did Abbot Charles presume on his growing friendship with Roosevelt to send him an autographed portrait of himself in formal vestments. With it, after reading that the president would be on an African safari after leaving office in the spring, he enclosed a blessed medal of St. Benedict, founder of the Benedictine Order. In his letter the abbot explained, “I enclose a medal of St Benedict which I want you to wear whilst out hunting in Africa. The good saint will protect you and bring you home safe.” In reply the president sent his own photograph inscribed: To Abbot Charles H. Mohr with the regards of Theodore Roosevelt Dec. 14th 1908. Abbot Charles responded in the very next mail, “Thank you ever so much for your photograph. I shall have it framed and keep it in my cell; I now include a medal for your wife also. It is fresh of me to take up so much of your time, but you are our President and I am your abbot. I pray for you every day.” The reference in the letter to “your wife” by Abbot Charles revealed a reticence in their relationship to go beyond his personal contact with the president; this was improved later, however. When Abbot Charles met his wife Edith and other members of his family at Oyster Bay, he later developed a real familial relationship with the Roosevelts and their sons and daughters, due to the location of Saint Leo’s dependent parish at Farmingdale, L.I., no more than ten miles distant from Oyster Bay. Abbot Charles’ official visits to St. Kilian’s, Farmingdale, took him there at least once a year. On one of his first visits from Farmingdale to Oyster Bay in 1911, T.R., as he preferred his friends to call him, was particularly gratified by Abbot Charles’ attention and concern for his 22-year-old son, Kermit, who was bothered by a periodic ailment. In a letter to the abbot, Roosevelt remarked, “I must tell you that Mrs. Roosevelt and I were really touched by both your manner and your words as you said goodbye to our son, Kermit.” The year 1911 was momentous time for both president and abbot; for the former it was a time to re-enter national politics, to revive his progressive policies for his Republican Party, and for Abbot Charles to defend the Catholic Church of the South from the “un-American” label the religious extremists were determined to apply to it. Following a speech at a Baptist church in Dade City entitled “Catholicism as a Peril,” Abbot Charles issued a rebuttal, printed at the Abbey Press and labeled “An Answer.” In the pamphlet, of which he sent a copy to T.R., by then contributing editor of the New York journal, “The Outlook,” the abbot refuted the outrageous claims of the lecturer by pointing out, “For twenty-five years and more you have before your eyes the Catholics of San Antonio, St. Thomas, and St. Joseph. What have they done to make you afraid? Do the murderers, the incendiaries, and the ravishers of women whose crimes fill the dockets of our county and circuit courts come from their midst?” Receiving a copy of Abbot Charles’ pamphlet at his editorial desk, Roosevelt replied by letter to the abbot November 20, 1911: “I shall take the liberty of reading your letter at the next editorial conference of The Outlook.” He continued: “That is a fine paper of yours, which I shall also show to The Outlook, and as you say, my dear Abbot, in it you kept your promise and you made it a friendly paper; and to use your final words, there is no cause to which I am more committed in heart and soul than the course of working to bring about among religious people that true peace which is founded upon justice.” He added. “When you come to New York again, will you not come and take lunch with us at The Outlook? I should like you to meet the editors.” In a subsequent letter T.R. queried, “Did you see that in the last Outlook I quoted your letter to me? My article was really along the lines of your speech, because it is a plea for reverence combined with liberty and charity among men of different religious persuasions.” There is no indication in their correspondence that Abbot Charles took up T.R.’s invitation to visit the offices of The Outlook, but the growth in warmth of Roosevelt’s letters prompted the abbot to advance his fatherly advice upon the president in a 1912 letter counseling him not to run for the third term. Roosevelt was already embroiled in a fight with President Taft for delegates for the upcoming summer convention of 1912. From his train as he thumped for delegates, T.R. wrote on April 4, 1912:

There is no question, from the tenor of the brief note that T.R. did not receive the advice from his mentor he perhaps expected to receive from not only a dear friend but a dedicated Republican. As history played out, he failed to gain the expected support from his party, so proceeded to accept the nomination from the newly organized Progressive Party a month after his rejection by the Republicans. As a sidelight to the wild political scene of the summer of 1912, T.R. as a Progressive was expecting a swing in the South from the solid Democratic front, particularly in Florida, where he felt he had solid support. Example: for seconding his nomination for president on the Progressive ticket at their August convention in Chicago, he named T.P. Lloyd, a respected barrister of Inverness, Fla., Democrat, and Confederate war hero. As it turned out, he received little support in the South, though garnering more national votes that Taft. In the spring of 1913, Abbot Charles wrote sympathetically, “I hope your and Mrs. Roosevelt are well. Now let us all watch Wilson try to run this country as if it were a classroom full of his pupils.” It is not likely that T.R. found amusement in his works. In any case, the campaign of 1912 took a heavy toll on T.R.’s life, particularly the attempted assassination, October 14, which effectively brought a premature end to his campaign. Even while carrying for the remainder of his life the assassins’ bullet, he embarked in 1914 an expedition to discover the hidden source in the Amazon of “The Rivers of Doubt.” Though he nearly died in the effort, he accomplished his mission. As a result, the change of the river’s name became Roosevelt, or colloquially, “Rio Theodoro.” With Abbot Charles embroiled in refutation of the increased attacks on the Church in the South, and T.R. concentrating on entering World War I to lead a volunteer division to Europe, their correspondence waned. T.R. was obviously not the rigorous, dynamic figure of the Spanish War of 1898, so his effort came to naught. One of his sons, Quentin, died as a war pilot in France, July 14, 1918. T.R. followed him in death at Sagamore Hill, January 6, 1919. Using Roosevelt’s private list of correspondents in 1920, the Roosevelt Memorial Association invited Abbot Charles to a membership. Abbot Charles replied immediately with a membership. Abbot Charles replied immediately with a membership for both Saint Leo College and Saint Leo Abbey. The Association Motto: “One flag, the American flag; one language, the language of the Declaration of Independence; one loyalty, loyalty to the American People.” Abbot Charles: The Man No one could have been more suited to his task as young (age 27) Father Charles Mohr took his assignment as head of Saint Leo College in summer of 1890 to take charge of opening the college and high school program that September. Nominally vice-president to Abbot Leo Haid, founder of Mary Help Abbey, Belmont, N.C., Father Charles took the reins of leadership immediately, and in less than four years, May 17, 1894, achieved independent recognition from Rome for his religious community with the rank of priory, with the transfer of membership of his entire community of priests and brothers with it. However, the ranks of Abbey for his community and Abbot for himself were not to follow until September 1902. Abbot Charles, born in Chillicothe, OH, January 24, 1863, was at heart an outdoorsman like his later friend, Theodore Roosevelt. From North Carolina, he brought his pet St. Bernard dog, Fritz, and at Saint Leo soon acquired his riding horse, Tom. With his outgoing, friendly spirit, he also showed an unfailing restraint in the face of bitterness or rancor in controversy. As abbot and college president, Abbot Charles served until the election of a co-adjutor and eventual successor, Abbot Francis Sadlier, in August 1929. Abbot Charles Mohr passed away after an extended illness on April 3, 1931. |